To answer this question, we must clarify and disambiguate some key terms: (1) proof versus evidence; (2) reanimation versus resurrection; (3) reason versus faith.

The term “proof” in this context carries two significant dimensions. First, it conveys certainty, necessity, and intellectual compulsion. By definition, to prove is to establish a fact. To have proof is to have truth guaranteed. Consider mathematical proofs or valid philosophical syllogisms – if the premises are true and if the laws of logic are honored, then the conclusion follows necessarily. The conclusion of a proof is not merely possible or probable but inescapable and apodictic.

It is worth noting that many people today understand “proof” primarily in legal terms – as evidence sufficient to establish facts in legal proceedings based on probability and persuasion rather than absolute certainty. Legal proof operates through standards like “beyond reasonable doubt” or “preponderance of evidence,” accepting that perfect knowledge is often unattainable. However, when we speak of proof in relation to divine mysteries, we are engaging with the classical philosophical and mathematical sense – proof as logical necessity that compels intellectual assent. This distinction is matters because divine mysteries require a different epistemological framework than human legal proceedings, which work with probability rather than absolute certainty.

The second dimension of “proof” often refers to something experiential – visible, sensible, or empirically verifiable. The etymology gestures towards this dimension; “proof” derives from Latin probare (to try or test). As the adage goes: “proof of the pudding is in the eating.”

Evidence is fundamentally distinct from proof. Proof establishes something as definitively true, whereas evidence points toward truth without being conclusive. This distinction is crucial to our inquiry.

In both senses, proof transcends mere evidence, leaving no room for doubt and often presenting itself to sensory perception.

Regarding “the Resurrection,” in reference to Jesus, this term bears a precise theological meaning distinct from resuscitation or reanimation. Someone resuscitated (as through medical intervention) returns temporarily to life but eventually dies. Similarly, Lazarus was reanimated – he died, miraculously returned to mortal life, and ultimately died again as all mortals do. But Jesus’s resurrection represents something categorically different: he died and rose to glory. His mortal body transformed into an immortal, glorified state incapable of suffering and death.

Speaking of the Shroud as “proof of the Resurrection” proves problematic because Jesus’s divinized humanity transcends empirical investigation. Even the disciples who stood in the presence of the risen Jesus could not perceive by natural reason alone the divinity of his divine person or the glory of his glorified being. Their reason was illuminated by faith.

The term “faith” refers to a personal adherence to God and a free assent to the whole truth that God has revealed (cf. CCC 150–55). The Resurrection of Christ is a divinely revealed dogma of faith, not the conclusion of a clever syllogism or the result of a scientific experiment. Of course, that is not to say that belief in the Resurrection requires blind faith. Since there are reasons to believe, faith is not blind. Faith and reason cooperate harmoniously. Faith is not anti-rational or sub-rational. Rather, it is trans-rational: it transcends reason without contradicting it. Supernatural faith perfects but does not replace natural reason, just as Christ’s divinity perfects but does not replace his humanity.

Given the nature of the Resurrection and the faith by which we hold this element of divine revelation, seeking proof of the Resurrection is ultimately futile. However, gathering clues and fitting them into a coherent meta-narrative about what took place is entirely legitimate. Indeed, it is the task of every good detective, every sincere truth seeker.

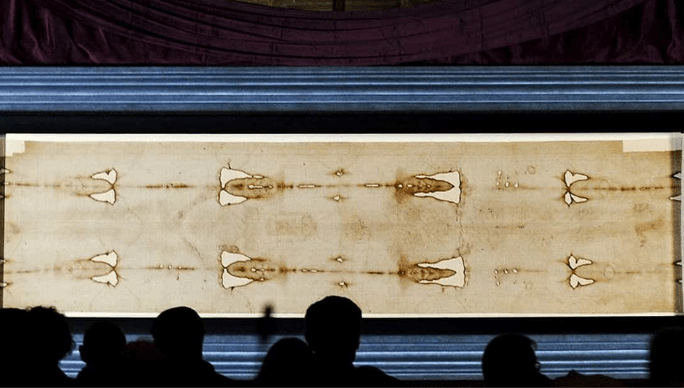

Let us consider seven remarkable yet uncontroversial features of the Shroud – presented in the order in which they were discovered – and, by abductive reasoning, seek the most likely or best explanation for them: (1) the image of the Shroud depicts a man’s body with perfect anatomical accuracy in both morphology and pathology; (2) the image functions as a photonegative; (3) it exists on a two-dimensional surface yet encodes three-dimensional information; (4) it affects only the surface of the linen fibers to a depth of merely 200–500 nanometers; (5) scientific analysis has concluded that the image is not the product of an artist – not a painting, rubbing, scorch, or photograph; (6) reproducing similar effects in laboratory conditions would require 34 trillion watts using UV excimer lasers; (7) and, despite being perhaps the most extensively studied artifact in history, no one has reproduced an image with identical characteristics.

These minimal facts make it unreasonable and fideistic to assert that the Shroud’s image results from ordinary natural processes. There exists no evidence supporting a purely naturalistic explanation. The cumulative scientific evidence points toward an alternative meta-narrative: the Shroud’s image may represent the natural effect of a supernatural event. As Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wrote through his character Sherlock Holmes: “When you have eliminated all which is impossible, then whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.” Applying this reasoning to the Shroud’s image, we find that as each naturalistic explanation falls short, the proposal of a supernatural origin becomes not merely possible but increasingly reasonable. To dismiss this explanation despite the failure of all natural alternatives would itself be an exercise in unreasonable fideism – a blind faith in naturalism despite contrary evidence.

In conclusion, while the Shroud does not provide proof of the Resurrection in the strict sense, it does give compelling evidence that some sort of supernatural event took place. As it happens, we have independent historical testimony about such an event. The Shroud stands as a remarkable consilience between scientific investigation and supernatural faith. We attain certainty of the Resurrection only by supernatural faith, which is always a free act. The unfurled Shroud is open to scrutiny – both scientific and contemplative. In this way, it profoundly echoes Christ’s own question, “Who do you say that I am?” Both the cloth and the Christ respect our free will while inviting us toward the fullness of truth revealed in and through the Risen One.